The Eye Of The Needle

Jim Schutte

This is my attempt to review roughly 17,000 years of human creativity in 10 minutes or so. It won’t be any sort of organized recounting. Rather a brief fly-by of creativity as I see it: minimizing cultural considerations and looking a bit closer, possibly at the artist’s motive. This will be a very narrow look at painting to shed light at a type of creative outburst that lies outside of the easily accepted. We’ll start at the Lascaux cave paintings and their two distinct styles. Then, remaining in Europe, we’ll skip to Modernism, specifically the Impressionists. We’ll find much beauty there, but for real answers, it’s New York. So hang on to your hats.

Lascaux has two very different types of mark making. The dominant type are drawn images of beasts, and through history, this representational type of work more than speaks for itself. But, over time, the nature, speed and intent of images changed, and today, sans sunglasses, this is the most reproduced image in human history:

But in the caves, there exists another, very different type of mark making with a very different motive: the stenciled hands.

These were to establish authorship and/or just pure expression

as there was no art market, no motive. Outbursts of creative

enthusiasm for being alive. It would take a while for this type of

Outburst to formally reappear.

Deconstructing Deconstruction

Roughly, around the middle of the 1800’s in France, representation started to become a real burden to artistic expression, and painting became less about the message, and more about the medium. This shift became known as Modernism, and developed into a deconstruction of direct representation.

It started, largely, with Impressionism, whose pictures are some of the most purely beautiful ever painted. It was a reversal for paint: instead of thin and sharp as a tool for imagery, it became smeary and thick with the pictures themselves presenting as physical objects. In terms of Lascaux, this signaled a shift from the beast with its drawn line, towards the hands with their pure spontaneous expression. But the very label “Impressionism” attempts to anchor this work in representation. These weren’t impressions, they were outbursts: of beauty and joy and delight. Outbursts of being alive. And, like the hands at Lascaux, they supersede specific information: they just beautifully are. And by backing off hard imagery, they allow wider association. Here we’re going to take another leap because, a century later, it seems there were again outbursts. This time, an ocean away in New York.

Everything that can be said about the emergence of abstract expressionism would be an understatement. The battle we see here, between these two men, historically takes us full circle directly back to the Lascaux Caves: back to the beginning. But this time it’s the death of the beast: the death of image making as a crutch, as an excuse to move the paint brush. DeKooning’s brush strokes weren't the problem. The problem was that he was trying to compose with them. His pictures are breathtaking and represent ultimate representational “abstraction”, but are transcended by Pollock’s simple purity. Indeed, much of the shock value from Pollock’s pictures arose from the method itself, flaunting the impossibility of image making. DeKooning at least had brush strokes.

Pollock’s pictures are, in fact, untouchable. They are the crowning glory of Modernism and mark its end. Representation had been deconstructed, and no amount of European sophistication could change that. What Pollock did was, well, he gave us purity of spontaneous gesture, echoing directly back to the Lascaux hands. As representations, the pictures have no motive and present ultimate grace. As difficult as he was, when he painted, it was with the innocence of a child. So the birth of American Art was also an ending, and the impact was such that it left both a great clarity, and great confusion. The result of this was a final deconstruction of the most fundamental aspects of representational signifiers, including color and composition itself.

The major players were; Johns with iconography, Warhol with celebrity, and Rauschenberg with assemblage and direct object making. Art is visual language and, at the top, artists own their space. These men basically closed off subject matter, as later on, Ad Reinhardt took color and composition itself to zero, and that left the stage empty.

The Eye Of The Needle

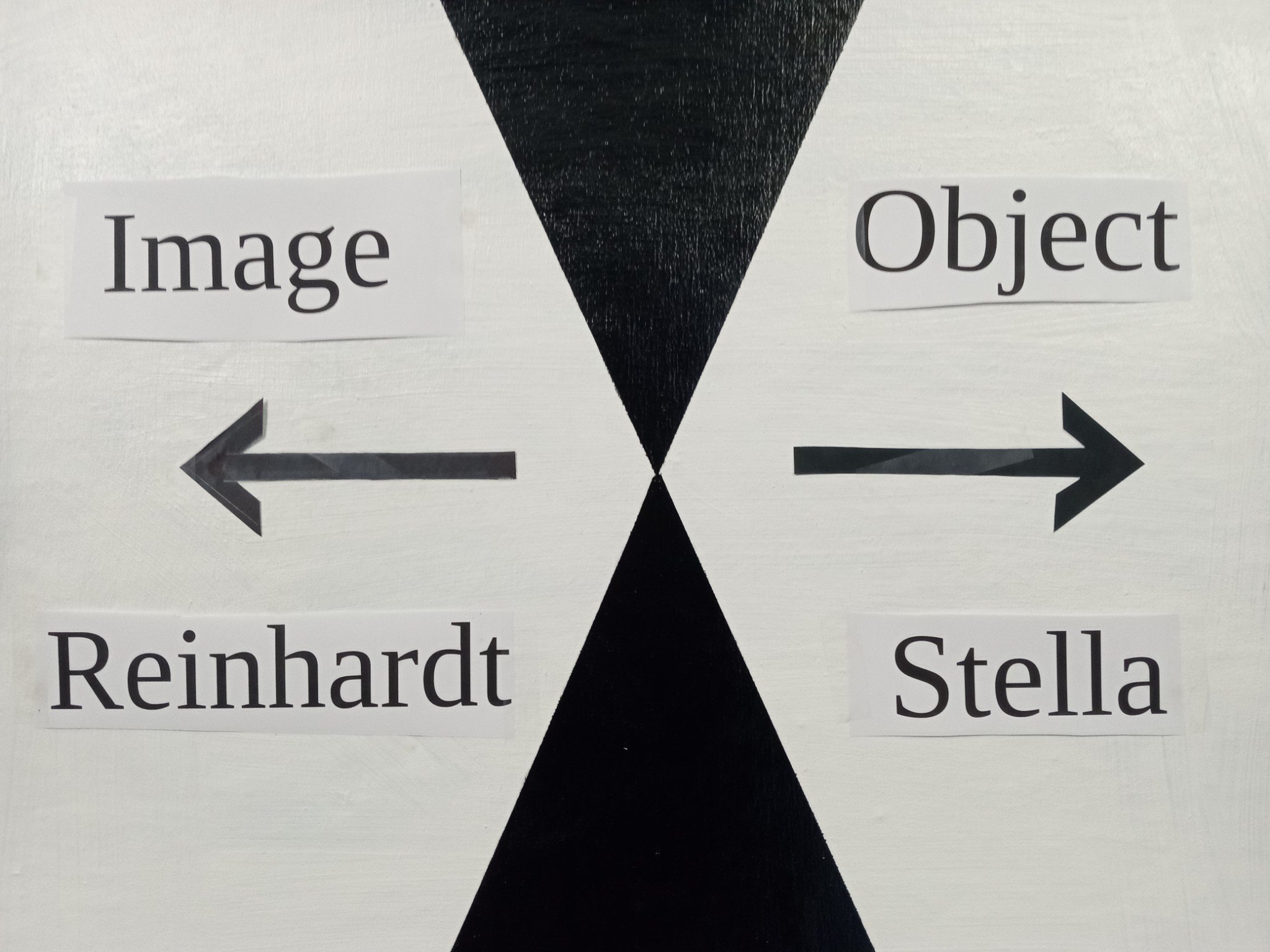

Minimalism refers to the pressure of this contraction on representational possibilities. But what happened next, born directly out of this zero point, can hardly be described as minimal. Things didn’t stop: they flipped. Image faded and “object” rose. This zero point is a clearing out of the old rules, and the starting point for new ones. And the #1 rule: Get Real.

On the left is Ad Reinhardt. His work is subtle, graceful and to solve its riddles, you need sensitivity to image. On the right is Frank Stella. His work is direct, physical and painted like a house painter. It starts minimally, but its physicality is maximal, it’s simply without illusion. It’s real. And this “Reality” is more direct, it’s more powerful. The subtle elegance of this “New Reality” seems invisible to most. People were shocked by both Impressionism and Pollock as affronts to their idea of image. The “New Reality” has escaped this, probably because pictures in real space, without even the intent of illusion, aren’t perceived as pictures. At least not yet. It’s possible that representation conditioned us to react, while “reality” demands something more of us and how we perceive.

Stella is a prodigiously productive personality born in the eye of the needle, and yet nothing, absolutely nothing about him is minimal. The difficulty with picture making in real space is linking gesture,

surface and form, (same issues, new rules). Stella is a structuralist,

good with surface and form, and when he gets gesture just right, well,

it’s grand.

One of the earliest examples with strong tendencies towards

“realist art” was, in fact, Picasso’s sheet metal guitar. Though partially

representational, it’s a good example of the clarity and visual strength

available in real space. And it too is a structuralist piece: strong on

form and surface, but here the gesture is of fragility: thin metal with a

snipped edge and a guitar image, a combination of old and new. The

big step is taking imaginative gesture to real space. Create real things

in real space with real materials and real processes.

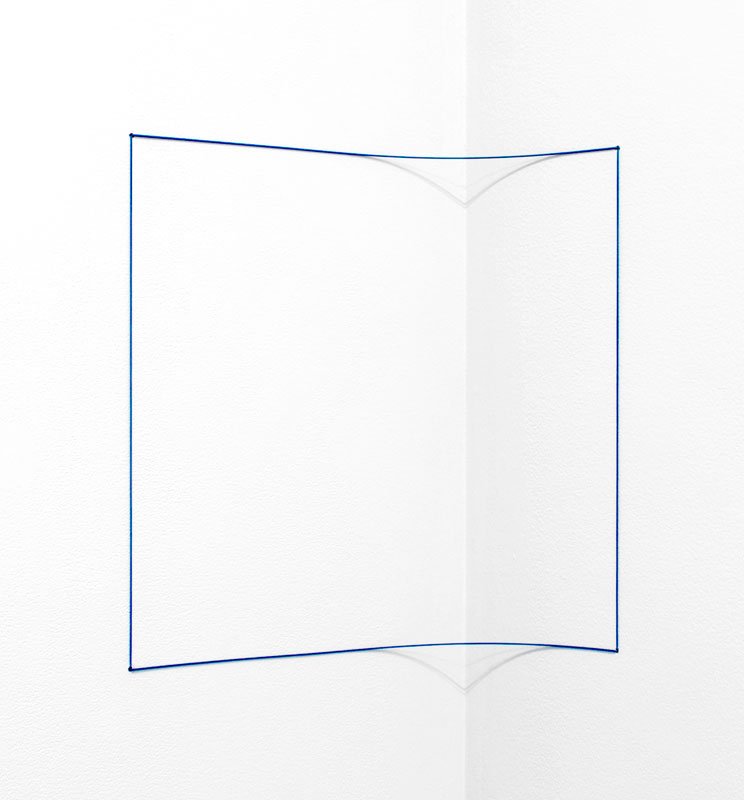

And that’s the thing with the term “minimalism”: it’s only minimal

near the needle’s eye, when the last vestiges of representation were

drained away. Or just after, when the new rules were being worked out

in the real world. Outside of Stella, most work has been “proof of

concept” type of stuff as artists dip their toe in, like Sandback’s line.

The question for them becomes where the heck they’re hiding the creative madness that Stella has in spades. In closing, just a reminder that this was a brief and narrow presentation with a very specific focus. It is, in no way, critical by omission. Thank you.

Jim Schutte, Long Island City, 2023.